Did you know that the Central intelligence Agency (CIA) was involved in publishing and distributing the epic Russian novel Doctor Zhivago?

I didn’t until I listened to the audio book version of The Zhivago Affair by Peter Finn and Petra Couvée. The title caught my eye because I had read the epic and long novel Doctor Zhivago as a teenager and had watched the movie at least twice. I knew vaguely about the novel having been smuggled out of the Soviet Union and published in Italy in 1957. What I learned from The Zhivago Affair was how the CIA was involved in promoting the book in Western Europe and getting travelers from the United States and Western Europe to smuggle the book into the USSR. The CIA had to find a printer in the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe to print the Russian-language original of the book and make it look like it hadn’t been published in the US, making sure not to use a type of paper stock common in the US, but not used in Europe. The CIA didn’t want it to look like it was involved. Instead, the CIA created fake cultural organizations to promote the book. The CIA got various different entities to be part of the scheme, including the Vatican at a cultural fair in Belgium!

I had no idea that the CIA hired people versed in the arts and letters to use literature as a way to influence communist countries in Eastern Europe. Modern spy craft these days has to do with cyber warfare not novellas, novels and poetry. The idea of using literature to bring down Communism seems romantic and idealistic, much like the namesake character of the book, Dr Zhivago, who was more of a poet than a physician.

See the film trailer:

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CGGr21PilKY[/embedyt]

Robbed of the Nobel Prize and money & mistress imprisoned

The The Zhivago Affair also spoke about the difficulties that Pasternak had in the USSR after he published Doctor Zhivago. Pasternak’s book was a wild success in the West and he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1958. The Soviet government pressured Pasternak to turn down the Nobel Prize. Pasternak died in 1960, five years before his book was made into a blockbuster film that is the 8th highest grossing film in history and without access to most of the money his book earned abroad.

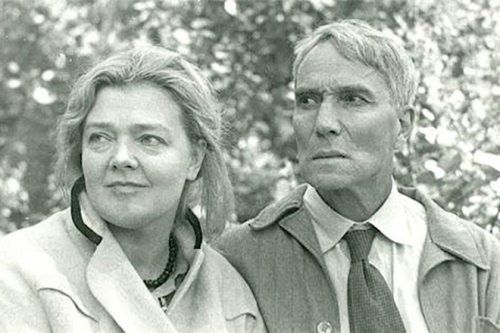

It was due to his mistress, Olga Ivinskaya, and other people who helped Pasternak, that his book was a success. Pasternak modeled Doctor Zhivago’s mistress, Lara, on Ivinskaya’s character. But Ivinskaya suffered immensely because of Pasternak’s success. The Soviet government sent her to a gulag (prison camp) twice for several years due to her association with Pasternak. Unfortunately, Ivinskaya’s daughter also was imprisoned in a gulag.

Theme song in my head

As I listened to the audiobook, I remembered where I was and how I felt when I read the book Doctor Zhivago when I was a teenager and what I felt when I saw the movie with Omar Sharif. Sometimes, I could hear the film’s theme song, Lara’s Theme/Somewhere my Love in my head.

The most memorable scene in the movie for me was when Zhivago and Lara travel through the snow in a horse-drawn carriage to a frozen home and find icicles inside the home and dust or snow on the table. Parts of this scene replayed in my mind as I listened to The Zhivago Affair.

See the film clip of this iconic “Frozen ice castle” scene:

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGd87xRnEAI[/embedyt]

Contrast of Soviet repression vs California spring

I listened to the audio book while walking through some Silicon Valley parks. There was scenic dissonance in what I was seeing around me and the stories of the gulags and repression. I walked past an overflowing creek and bushes, grass and new spring flowers as I listened to the narrator describe how Pasternak’s writer friends, such as Anna Ahmatova and Osip Mandelstam, were repressed by the Soviet government.

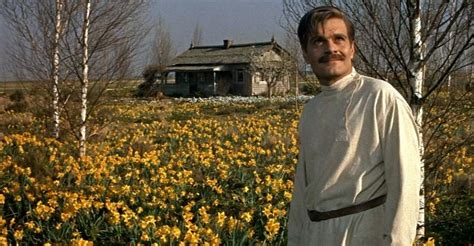

My springtime scenery looked more like this scene in the film when Dr. Zhivago was walking in a field of flowers than the gulag where Mandelstam died.

Although the stark contrasts between what I was seeing and hearing were sometimes distracting, they made the book more poignant and memorable than if I had just read the book while sitting at home.

As I was looking for a lemon to pick, the audio book narrator described how the wife of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, Nadezhda Allilueva, had committed suicide.

On another day, while taking a new path in a park that I had been to many times, I listened to the description of how the novel was promoted in the West. I stopped when I saw a man picking something from a tree. I stopped the audio book and took off my headphones and asked the man what he was picking. He showed me the fruit and I didn’t recognize it. He checked his Arabic-English dictionary on his phone and said, “It’s a green almond.” He let me try the sour nut. He told me he was from Damascus, Syria and was going back soon. I asked him if he was afraid of going to Damascus given the war and he said,”The situation isn’t as bad as what we see on TV.” I went from listening to audio book about Soviet repression in the 1960s to sharing sour green almonds with a Syrian man going back to a country known for its political repression and civil war. The irony was not lost on me.

Multi-sensory experience of audio books

Besides getting through audio books much faster on audio than by reading a book, I like audio books because I often remember poignant parts, scenes or quotes from books when I associate them with places I walked or drove by when listening to the book. The audio books come alive because I am having a multi-sensory experience. While passing by fennel bushes, a lemon tree, sour green almonds, poppies, a landmark, business or other place, I might associate their look and smell with a book I’ve listened to. This way, the books live on within me and around me long after I have listened to them.

Listening to a description of a foreign world that I had to imagined or, in my case, a world I knew from my parents’ stories of Soviet life and my own time traveling and living in the former Soviet Union, was also multi-sensory experience. I was simultaneously remembering the past, imagining the past as described to me by others, looking at what was around me and paying attention to the story.

Even though I left the Soviet Union as a young child, the stories my family members have told me about their lives during Soviet times are very vivid. For example, I can imagine what it was like for people who had to read underground (banned) literature overnight or over a couple of days in their kitchen (and maybe by candlelight) before they had to pass it on to somebody else.

Unfortunately, during one occasion while listening to the book, I was driving to my friend’s Brazilian music show by Stanford Hospital while I also had the Google Maps app on my smartphone directing me to this new location. Just as the book was describing how Boris Pasternak had died of cancer, how people in his family were taking care of him and how the people in his is right or village reacted to his death into his funeral, the female voice on Google Maps was voicing directions, “In a ¼ mile, turn right,” “Make a U-turn,” etc. Since there was no sign for the restaurant, I had to listen to the directions several times before I could find the restaurant. It was as though listening to the Google Maps directions made me dishonor Pasternak on his deathbed, even though he died before I was born! When I arrived at the restaurant, there was a group of filthy rich Russians getting drunk on very expensive alcohol and dancing in a conga line to Brazilian music — a stark contrast to the Soviet reality Pasternak had faced.

The next day, when I was making my breakfast and taking out the dishes from my dishwasher, I listened to the section about his death and his funeral again, without any vocal distractions. I owed the author a respectful listen to his death.

Can books change a repressed country?

As someone who loves literature and the arts, I would like to think that books, movies, music, theatre and other arts can foment change. However, Western literature and culture may have only influenced a small portion of the Soviet population that were avid readers and keen to consume banned literature. I don’t think the CIA was going to cause a revolt by getting a small fraction of the population to see a negative side of communism via the book Dr. Zhivago. But in the 1960s, the chief US spooks didn’t have the tools of cyber warfare, industrial espionage, social media and other modern forms of spycraft at their disposal. Literature was one of the forms of infiltration they tried to use.

For those who are interested in international affairs, literature, life in the former Soviet Union and spy craft, this is the book for you. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that has so blended these interests of mine. The book also speaks about the anti-Semitism that Boris Pasternak faced in the former Soviet Union.