The scalpel cut into my father’s chest. As blood oozed out of the wet, pink flesh, the surgeon said to me, “Tell your Dad I’m going to cauterize his skin to prevent infection.”

My Dad, who speaks limited English, was yelling “HELP” in Russian, from the pain. I had no time to consult an online Russian-English dictionary for the words “cauterize,” “scalpel,” and “stitch.” I had never seen human flesh cut open before and found myself grasping for the right words to calm my Dad down. I told him that he was getting thread in his body and that the doctor was cutting him with a knife and not to be worried if he smelled or saw smoke!

The doctor thought I was going to faint because it was my first time seeing a human body cut open but I couldn’t afford to lose consciousness because my Dad was relying on me to not only interpret, but also explain and console him as he was in pain.

This is the reality for family bilingual caregivers. One day, we’re de facto surgical interpreters and the next day we’re explaining social distancing and Covid precautions. Many times, we have to improvise because we lack the specific vocabulary, taking two or three sentences to explain one word or phrase. Unlike professional interpreters, we don’t have the time to learn specialized vocabulary before interpreting because we often have no idea what kinds of situations we are going to be in or what kinds of words may be used. Multilingual people are not natural translators or interpreters.

Extra burden during pandemic

Besides the women bearing the extra burden of the unpaid labor of childcare, cooking, house cleaning, and distance learning due to the pandemic, bilingual caregivers are another huge segment of the population with onerous unpaid family workloads.

Bilingual children and family members in the 20% of US households who don’t speak English at home carry a heavy burden of caregiving, interpreting, and translating in our Covid-restricted world.

The linguistic mental gymnastics of translating written documents and interpreting at meetings and medical appointments can take a huge toll on our mental health.

It can be taboo to even say that caregiving for elderly relatives is a burden because children are supposed to take care of their parents since their parents brought them into this world and raised them. There’s a major difference between adults choosing to have a child and adult children tasked with dealing with parents many health problems, many of which are self-inflicted due to poor diet, lack of exercise, smoking, Type 2 diabetes and more.

I am breaking with the taboo. Caregiving for elderly relatives can be a huge burden and it’s even harder when there’s a language barrier. There. I said it. Let’s move on and look into why it’s so hard to be a bilingual caretaker during the pandemic.

It’s super hard, even for me

I came to the US as a child from the former USSR and have personally experienced how much more difficult it is now to be a caregiver to both of my parents (in their 80s with many illnesses and cognitive problems) than it was before the pandemic.

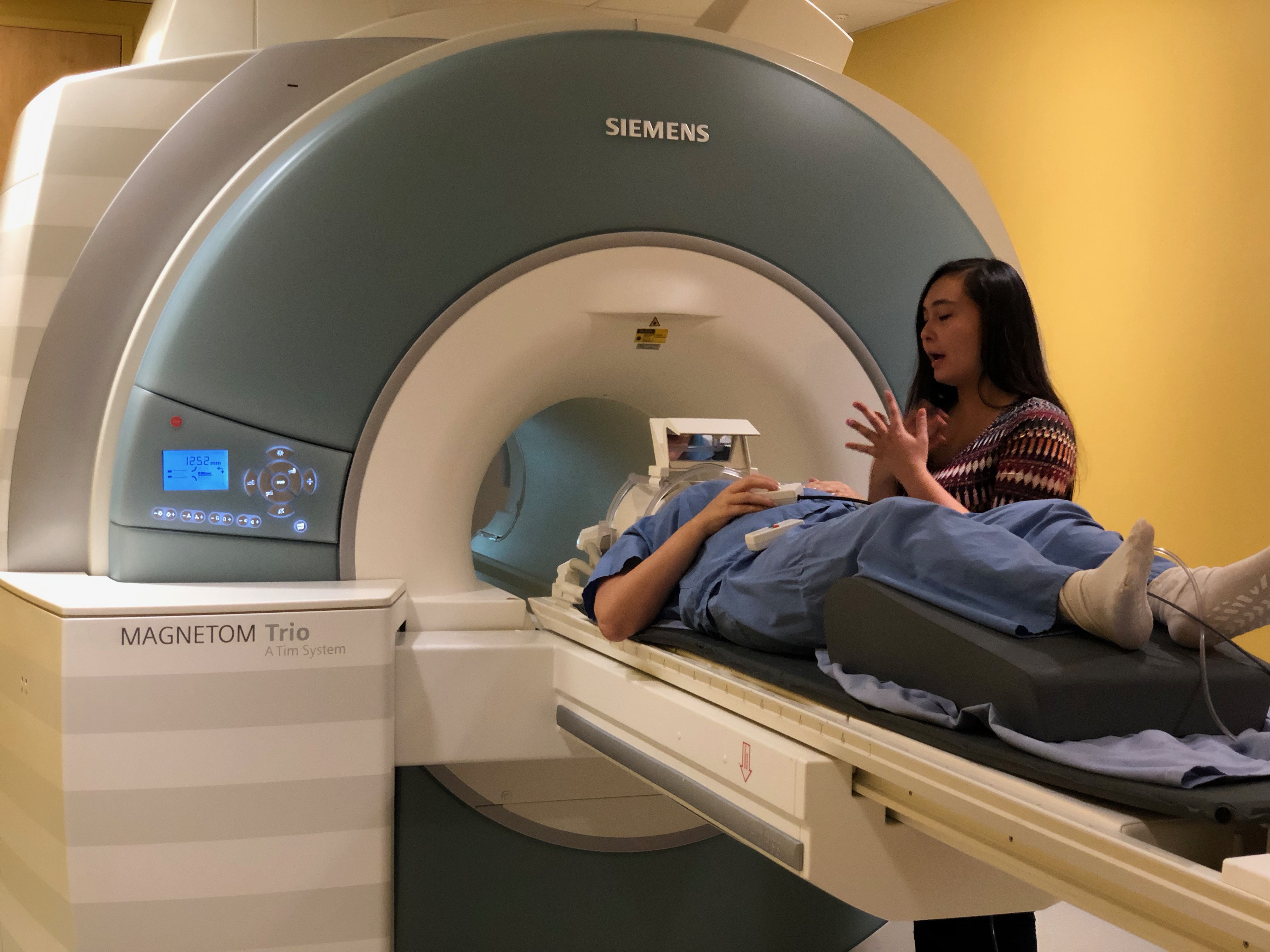

Being a hyperpolyglot (I can speak in eight languages), I know how hard multilingualism is on the brain. I was part of an MIT study on the polyglot brain that showed how my brain works when listening to different languages. The MIT study was done with an fMRI machine and showed that it takes my brain less work to listen to English, my second, but strongest tongue, than it does to process Russian (my native tongue) and Italian, my 5th language. Switching languages is extra work for my brain and can lead to sensory overload. Due to the pandemic, my brain is more tired than before and it’s harder to process other languages. There is no doubt that my language skills have weakened. Faced with explaining new and complex information about the virus to both of my parents using medical and epidemiological vocabulary I am not used to makes it all the more difficult to remember how to properly decline nouns, adjectives and pronouns in Russian’s six cases.

Despite this mental difficulty, I have family responsibilities that go way beyond proper conjugation.

Roles of bilingual family caregivers

We usually think caregivers are adults who take care of elderly people in their home with cooking, bathing, toileting, cleaning, and other tasks. However, many children of immigrants have been caregivers, interpreters, translators, and all-around guides for our parents since we were children, sometimes as early as in elementary school. I began to research election issues and fill out my parents’ sample ballots when I was 11 or 12 years old.

The unpaid language work done by family caregivers is sometimes paid in headaches and stress, while professional interpreters and translators earn good salaries:

- United Nations conference interpreter, $483 – $725/day

- Stanford Hospital medical interpreter, around $40/hour

Due to a shortage of medical interpreters, parents may have no other choice but to force their children to interpret medical vocabulary with which they’re not familiar. Some medical offices may only have medical interpreters via telephone or video. For some elderly and those with hearing problems, they need a live interpreter next to them because they can’t hear video or telephone interpreters, even if they are wearing hearing aids.

Master explainers, all the time

Professional interpreters and translators are usually only supposed to convert the words that are said or written from one language into another. Bilingual caregivers do much more than just interpret or translate. They have to explain the context, background, impact of what is said or written and be our parents’ main advocates. For example, translating a Covid mask sign requires more than only translating the words. The bilingual caregiver also has to explain what a pandemic and virus are, the role of masks, and the fines for not wearing a mask. In Los Angeles, communities who didn’t have access to news in their language did not understand why people started wearing masks.

Not only do caregivers bear the brunt of the interpreting and logistics, they are also the unlucky messengers of bad news and are the object of their relatives’ anger.

Imagine this scenario. When Kaiser Permanente HMO in California started offering Covid vaccines to those over 80, they had no website to make appointments. Your phone was on speakerphone while you waited 5 hours on hold while working from home to make an appointment for your family member. Two weeks later, the appointment was cancelled when Kaiser ran out of vaccines. You have to explain that your relative has to wait an indefinite amount of time to get the shots. Imagine receiving the anger, frustration and confusion of your relative who has been stuck at home for a year and wants to get their vaccine so they can see their grand kids whom they haven’t seen in a year. All of that person’s anger is directed to you, even though it’s not your fault.

Constantly explaining the who, what, why, how, and where is exhausting on its own. The role of Master Explainer also forces us to always think about what our family members don’t already know or understand. This can lead to empathy overload, where we neglect our own needs and boundaries because we are constantly catering to the many needs of others.

Dual burden leading to stress, burnout

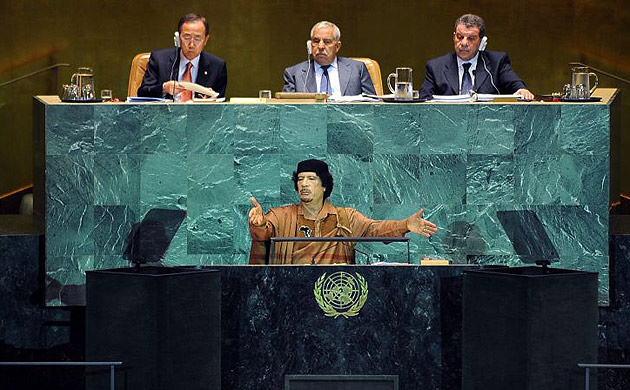

Switching languages is mentally and physically exhausting. Simultaneous United Nations interpreters work in teams and take breaks for long conversations. In 2009, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi’s interpreter collapsed and stopped interpreting after 75 minutes of Gaddafi’s 96 minute speech! Family bilingual caregivers may feel like collapsing but may not have that luxury because they have no one to replace them. I often have to tell people to stop talking so I can interpret, otherwise I can’t remember everything that was said. Plus, I need a mental break from listening!

Coupled with language responsibilities, caregiving during the lockdown is dramatically more difficult because there is less or no outside support. To avoid exposure to the virus, families are understandably hesitant to hire people to enter the home to do cleaning, cooking or home health work. Community and senior centers that have activities, sports, meal programs, and social worker support are all closed.

Caregivers of family members with cognitive and memory problems can easily tire from having to remember the details of their parents’ medical history and medications. Those with memory problems may repeatedly ask the same questions and make the same comments, severely aggravating their caregivers. If a caregiver has to continuously repeat the same information to one’s family members, it can feel like a nightmarish bilingual re-run of Groundhog Day over and over again.

If the parent has both memory and hearing problems and their hearing aid batteries stop working or the hearing aids are full of wax and the parent can’t hear, the situation gets much worse. The caregiver may have to shout or speak very loudly. Imagine yourself speaking so loudly about your parents’ hemorrhoids or diarrhea in a medical office when other patients can hear you and may stare at you for being so loud. These situations can be mortifying as well as stressful.

These language burdens increase with age. My mother used to be fluent in English but now she has trouble understanding people unless they speak slowly. I often have to interpret for her in situations where she used to manage on her own.

For caregivers in the sandwich generation, with children who need to be homeschooled and elderly parents who need language, material, and emotional support, their multiple family responsibilities may be unbearable because the caregivers have little time to themselves and are constantly responsible for other people.

Caregiver burnout is real. Caregivers can die before the person for whom they are caring because their bodies and brains are overwhelmed. For those with the dual duties of caregiving and interpreting, our burnout risk is high and we risk losing our jobs.

What do we do to improve our mental and physical health?

Possible mitigation strategies

We can’t erase all of our language responsibilities, but we can lessen the load.

- Technology

Teach your family how to use translation apps. Some can translate both written and spoken language, including a continuous conversation. In case you’re in an area with limited or no WiFi, you can download the language dictionaries on your phone and use them offline.

Currently, the only way I can communicate with my father in his nursing home is through a glass door or video calls using the Live Transcribe app on my tablet. My father reads what I say on the screen in Russian and English. The app can’t be used offline and requires an internet connection.

2. Boundaries

Setting boundaries can be hard in cultures where children are expected to take care of their parents until their death. If you’re an introvert and your brain feels like it will explode from listening to chatterboxes or extroverts who don’t understand how tiring it is for you to listen to them, you may need professional intervention. With the help of a bilingual therapist, you may be able to get your parents to understand how your multiple family tasks impact your mental and physical health. Encourage your parents to socialize via phone or video calls with other people so that they don’t rely on just you for all of their companionship needs.

Limit when and for how long you interpret. Maybe only interpret during medical visits or other necessary appointments, but not in social settings. Or set limits on the amount of time you interpret in social events so that you have time to enjoy the function. Ask others to replace you when you need a break.

3. Rely on others

Ask friends and family for help with activities that can be done without entering the home such as:

- gardening

- shopping

- food preparation and delivery

- tax preparation

- tutoring your children online

If you’re in a multi-generational household, recruit your teenage children to:

- walk their grandparents

- wash your car

- do light cooking and housework

assist grandparents with medications, measuring blood sugar and blood pressure or other simple medical tasks

4. Outsource food preparation

Buy prepared foods in bulk from restaurants, delis, and stores. Check if your parents qualify for food delivery programs such as Meals on Wheels.

Although it’s more expensive than preparing the foods myself, I have learned that I have to cut corners somewhere to maintain my mental and physical health. I don’t have 3 hours to prepare a pot of Russian borscht beet soup, but I can pay the cooks at the Russian delis and stores for soups and other specialties.

5. Avoid non-essential interpreting and explaining

To evade the role of interpreter/tour guide, I don’t go with friends and family to ethnic restaurants, stores, neighborhoods or social events where I know the foreign language and my friends don’t. Just having time to myself where I can soak in the local language, for example in a mostly Spanish-speaking Latino neighborhood, is important for me. I can communicate in Spanish without the need to constantly explain conversations and context. I can just be without always having to think about what the other person may or may not understand and need to know.

6. Take time for yourself in silence

Especially for introverts and highly sensitive people, time to be alone and decompress in a quiet place is vital to mental sanity. Go to a local park or beach or take a walk just to smell the roses and enjoy the scenery without listening to music, podcasts, audio books, and other media. Silence can truly be golden and medicinal.

—

There’s no easy solution for our dual burden. The first step is to recognize that we’re not alone. Our stress is real. We have to take care of ourselves.